Distance: 25 years since the death of The Triffids’ David McComb

In the late ’70s and early ’80s I lived a very long way from the leafy Peppermint Grove avenue where a high school student named David McComb got together with a couple of mates and his brother to form one of Australia’s most famous post-punk bands, the Triffids.

I grew up in outer suburban Perth and while I too had siblings, we barely tolerated each other and the closest we got to collaboration was the four of us agreeing to play Monopoly.

By the time I’d turned fifteen, I was comatose with boredom and trapped at the wrong end of a more-than-an-hour, two-bus journey to Cottesloe beach; emotionally adrift in an endless, concrete suburb that the planners called ‘dormitory’ for good reason.

I existed for Sunday night’s ‘Countdown’ and like many of my generation, recorded my favourites on a cassette player positioned in front of the television or at other times, direct from the radio. Perth was a greatest-hits, cover-band city and it felt inconceivable that any group from my town might make it big overseas.

At our local pub, the Lynwood Arms, you could listen to bands recreate the latest pop songs, or a DJ playing the actual top 40, and feel as comfy as a Hawaiian shirt at a barbecue. Everyone I knew said nothing original came out of Perth.

Or maybe it was just Lynwood.

‘just a dot on the map‘

At high school, we worked out early that nobody expected much of us. As long as you mostly turned up when and where you were supposed to, the adults – especially the teachers – left you alone.

To avoid getting your head smacked in or your lunch money nicked, you controlled your bladder for an entire school day so you didn’t have to go to the girls’ toilets, where the pencil-skirted ‘Moles’ ruled in a Winfield Blue smoke-haze of terror.

If you learned the difference between onshore and offshore breezes and called yourself a ‘Surf’, it gave you somewhere to belong when the other choices were the pale-faced, shaven-headed ‘Skins’, or the grimacing, black-booted ‘Rocks’.

And if the distance on public transport from Lynwood to Cott felt interminable, it was nothing compared to the socio-economic divide separating us from the western suburbs’ private school girls with their magazine teeth, glossy hair and designer label bathers.

‘if you can leave, then leave it all‘

Back then, if you didn’t want to die of numbness, you made a plan to escape Perth as fast as your white Dunlop Volleys could carry you. The Triffids did it for all of us: they packed their coats and scarves and headed east, then to London and Europe where they found success.

They hung out with Nick Cave and the Ramones and played festivals like Glastonbury and Roskilde. Towards the end of the ’80s, local Perth radio stations found room for ‘Wide Open Road’ and ‘Bury Me Deep in Love’ on their adult-oriented rock playlists.

But when local cover bands added Triffids’ tunes to their repertoires, the band had truly come home, transformed by the approving gaze of the world into something we would proudly claim as our own.

The Triffids’ success seemed effortless, yet preposterous. You mean all that talent and coolness was born here? It made you feel like you too could have been brilliant, if only you’d given more of a fuck about anything.

‘...and years before his time‘

Friday, 2 February, 2024 marked 25 years since the death of David McComb. He died aged just 36 after multiple health issues, some of them rock-star related, and left behind a substantial discography, poetry, unfinished songs, family, friends, and thousands of devastated fans.

To me, the band’s strength has always been in its combination of accomplished players, but there’s no denying the incandescence of their front man. Watch him here and you might be reminded of Nick Cave, Michael Hutchence or even Mick Jagger, but McComb was unique: brains, balls and a voice that could simultaneously seduce you and incite you to revolution.

Every year on this sad anniversary, people across social media share their memories of David McComb and their favourite Triffids shows.

My recollections from my late teens and early twenties are pretty hazy, lacking in names, dates and wit, fogged by time and an unwillingness to travel the emotional distance.

I don’t remember much: getting drunk at the Shents, getting drunk at the Raffles, getting drunk at the Stoned Crow. The nauseating smell of bodies, stale air and coconut tanning oil inside the old MTT buses. The OBH Sunday session after a day on the beach, drinking beer after the sun had burned us, leaning out of the windows to cool our flaming skin in the late afternoon onshore. (This pic is one of the few from that time I didn’t throw out – possibly around 1982)

‘a hell of a summer’

My relationship with the Triffids didn’t get serious until I was well into my forties, in the summer of 2011.

It was a rebirth kind of summer, in which my poorly constructed self burned down in a fire I hadn’t prepared for. I bought a sarong, and a CD of the Triffids’ seminal 1986 album, Born Sandy Devotional, and David and the rest of the band sat in the back seat and sang while I drove up the coast. I hadn’t been to the beach in more than a decade, but that summer I spent days, weeks, immersed in salt water.

On those drives, I discovered new depth in McComb’s lyrics. He writes about love, loss and distance, and more often than not, his words about our postcard beaches are a tidal pull that exposes something darker.

In ‘Estuary Bed’, clever repetition describes an unending Western Australian summer: ‘washing the salt off under the shower/and just wasting away, wasting away/the hours and hours and hours’.

At the start of ‘The Seabirds’ we’re under a sky so warm and bright that ‘No foreign pair of dark sunglasses will ever shield you/from the light that pierces your eyelids’, yet by the end we’ve experienced a visceral loss: ‘They could pick the eye from any dying thing/that lay within their reach/but they would not touch the solitary figure/lying tossed up on the beach’.

In 2011 my parched bones couldn’t get enough of the ocean and it was McComb’s seascapes that explained the doubleness of love and loss to me when I had no words of my own.

‘beautiful waste’

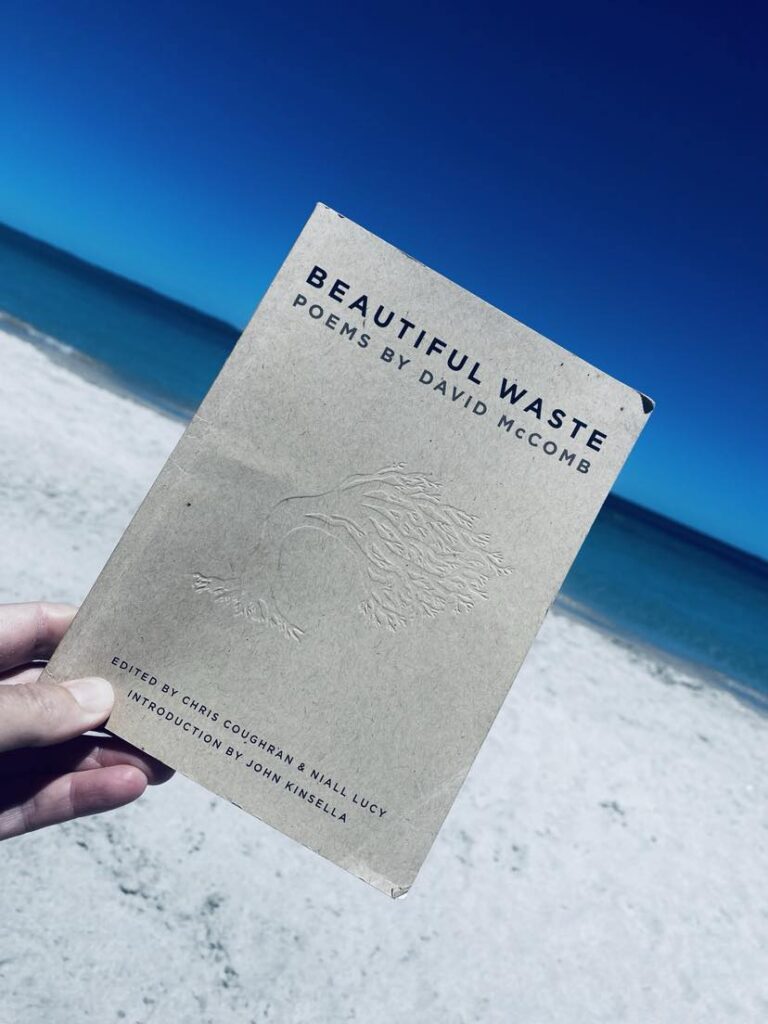

In 2009, Fremantle Press published a posthumous collection of McComb’s poetry titled Beautiful Waste. I rescued a copy from a second-hand shop at the end of my magical 2011 summer.

Imagine my delight to find a poem called ‘Ocean Beach Hotel’ – McComb’s take on my old haunt, the OBH: ‘Lead-enriched exhaust fumes/pizza belch and spittle resin/do battle/with the stiff sea breeze and sand/particles whipped into flight’. David McComb might have been leaning out of that same window but unlike my crowd, he was paying attention, writing it down and making art out of an experience as ordinary as mine.

Much like his music, the distances in David’s poetry are emotional and geographical. In ‘The Mistake of Returning’, he captures the pain of revisiting the past: ‘No one had spoken to warn me/or advise me of the grief/that was lodged in these pavement cracks/as splinters of doubt or longing’. Did he feel the same way about Peppy Grove as I did about Lynwood?

As acclaimed writer John Kinsella writes in the slim volume’s foreword: ‘it is almost bizarre that David McComb is not yet known as a significant Australian poet.’

‘is that still you?‘

Since McComb’s death, the remaining Triffids have lovingly tended to his legacy. They play regularly alongside guest vocalists including Rob Snarski, J.P. Shilo, Gareth Liddiard and others.

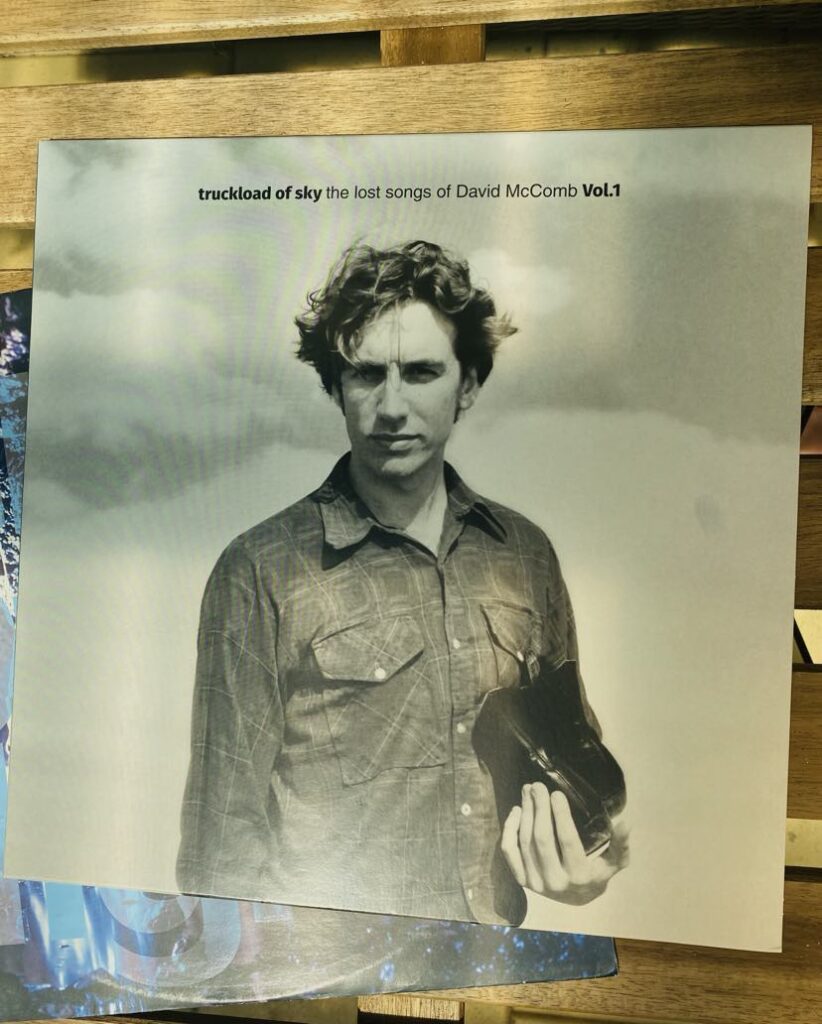

In 2020, an ensemble of collaborators released ‘Truckload of Sky: the Lost Songs of David McComb Vol 1’ (pictured above) and 2021 brought the wonderful documentary, Love in Bright Landscapes. Watching it, I felt like I’d been invited into someone’s front room to watch home movies of a much loved friend.

I wanted to be uplifted, but I was overcome by feelings of emptiness and loss. I grieved for the songs not written, the poems unformed, the stories and novels we’ll never read because David McComb died too young.

A quarter of a century after his passing, arguably the most recognisable of McComb’s songs continues to top ‘best of’ lists. It’s curious that some of us still can’t describe ourselves here, on the sandy edges of Aboriginal land, without the help of ‘Wide Open Road’.

Perhaps the song’s genius is that its speaker is lost, grieving, small, and above all, placeless. We have all been there.

©2024 Sharron Booth